A HANDFUL OF GRAVITY

What do we still have in our hands, when we experience our own gravity first and foremost and find ourselves orbiting within the same space? In the exhibition A Handful of Gravity at Christine Mayer Gallery, Andy Hope refers to his paintings as Orbital Hypertrophies. We probably won’t return from this orbit hypertrophied, but weakened in weight and body tissue. Yet, we also spin within the waltz pushed upwards by Stanley Kubrick, while the gravitational pull that binds us to Andy Hope is the opposite of the force which physically ties us to earth. In a 2000 text, such consists of the “ease of making rather than producing”. And when Lothringer 13 displayed Raumvorstellungen in the same year, Andy Hope showed a work of kissing galaxies, among others.

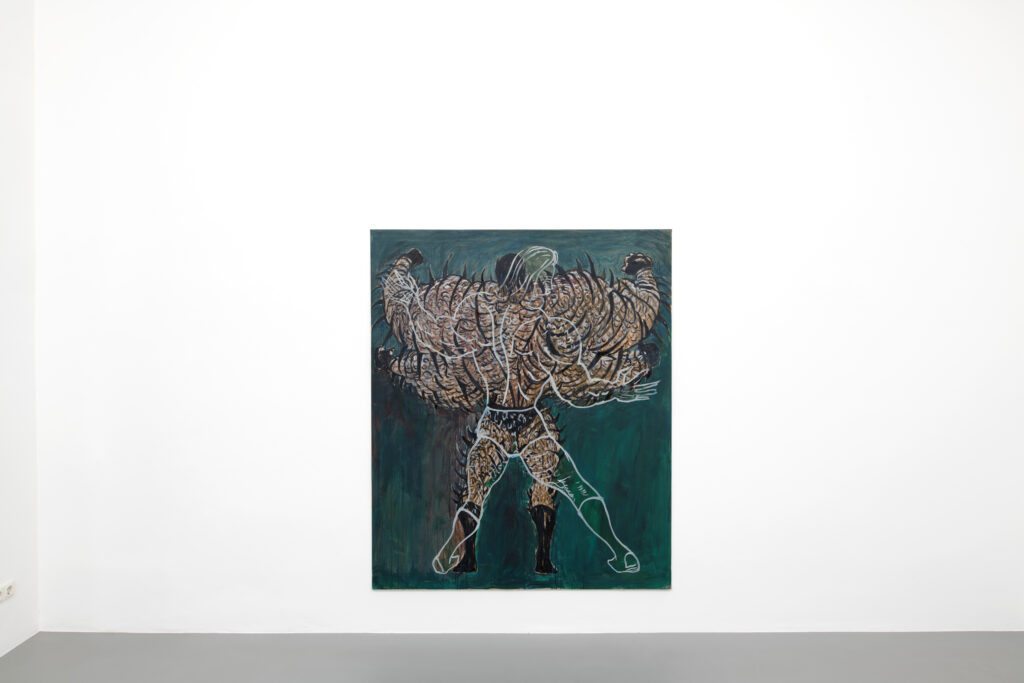

The 2022 titles point to the cosmos and physical bodies, not loneliness or melancholy. And finally, Andy Hope begins where the production of the culture industry ends: the works Orbital Hypertrophies are painted, but only to a certain extent paintings. Anyone who sees Tintoretto also sees Jack Kirby.

Everyone, who is drawn to this can grasp its attraction through what Sergei Eisenstein refers to as the montage of attractions. Andy Hope also uses his tools as “an arrangement of firing pins directed by virtue of their formal peculiarities towards the consciousness and feelings of the spectators”. His art thus enters the “circle of influencing arts”, to which, according to Eisenstein, theatre does not belong, but the circus does very well indeed. Andy Hope once called one of his drawings Nihilist Circus, thereby asking the question of what is actually to be achieved? Provocations can only increase the heaviness that weighs upon the present. On May 11, 2022 Boris Groys said: “We live in a civilization that only accepts the present as reality. Locked up in our generational dungeons, we only live in the here and now.” Every day, a professional teenager throws a stone into the same pond. For Andy Hope, however, it is not about suffering, but a free move, allowing illusion and disillusionment to become one – to become one in the present. The works Orbital Hypertrophies reveal the struggles that will continue even in the dungeons. Man seems alone with himself, but is also confronted with the other, who he is, too. In fact, it leads to the “spasmodic unclamping of all of the wings of the soul” that Nietzsche saw coming.

Above all, however, the figures are not alone because they are shown interwoven with the other, namely the pictorial space that surrounds them like outer space.And this web isn’t nearly as rigid as the lattice that is connected to the dungeon. It is true that Andy Hope resorts to a medium in which the heaviness and mechanics of the Western image production have manifested themselves in the modern period, especially in the centuries-long reproduction of copperplate engravings. But unlike Albrecht Dürer, Andy Hope does not primarily use crosshatching to describe bodies, but emptiness instead. The picture space seems to be filled less immanently but is opened up transcendently. It can be pointed out that Günther Förg’s grid describes Munch’s bedspread, while Hans Hartung’s pointy, reed-shaped brushstrokes depict outer space. But this clue misses the moment which reveals itself as A Handful of Gravity, as does the clue that the poet Arthur Cravan fought in the boxing ring. Rather, this space and this figure interact with each other in a way, which allows them to alternately appear opaque and transparent. This impact on the viewer, or that we encounter not just an image, but a will that we think we not only see but also hear, indicates an equilibrium so general that it remains unnoticed until it is is disturbed.

The Chinese philosopher Zhao Tingyang explains that around 2300 BC the legendary ruler Zhuanxu ordered an “earth’s contact with the sky to be severed”. And Christianity could be described as “a worldwide lasting interruption of the contact between heaven and earth”. Still, the 2020 book is called Alles unter dem Himmel (Everything beneath the Sky) and the subtitle is Vergangenheit und Zukunft der Weltordnung (The Past and Future of the World Order). Towards the end, however, the author admits that an orderly world does not simply mean living a good life. Therefore, he closes his book with a reference to a completely different book. “Archaeologists have discovered numerous ancient writings in tombs, the Book of Music was not among them. Its loss may need to be taken as a metaphor.” Many speak of the disenchantment of the world, while a few say it becomes an impossibility without enchantment. Andy Hope adds to the enchantment when he creates images and music at the same time.

Berthold Reiß

Translated by Melanie Waha